April 2014 • Volume 102 • Number 4 • Page 188

Thank you for viewing this Illinois Bar Journal article. Please join the ISBA to access all of our IBJ articles and archives.

Employment Law

Helping Employers Avoid Harassment and Retaliation Claims

This article argues that a clear chain of command and well-drafted anti-discrimination policies can help employers ward off retaliation and hostile work environment claims. It offers tips to help you counsel your employer clients.

T wo rulings issued last year by the U.S. Supreme Court make it harder for workers to bring two kinds of employment discrimination claims that have been especially challenging for employers - those based on a hostile work environment and on retaliation. A hostile work environment is one in which an employee is subjected to unwelcome (and, of course, discriminatory) conduct or comments, which are directed at the employee because of his or her race, color, religion, national origin, or sex. Retaliation is, in essence, adverse treatment of an employee for filing a discrimination claim or opposing discrimination.

At the federal level, employment discrimination claims are generally governed by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ("Title VII"),1 which continues to evolve through judicial interpretation. Since the twin cases of Faragher v. City of Boca Raton and Burlington Industries v. Ellerth, the burden of proving employer liability for "hostile work environment" harassment has largely depended on two questions: (1) whether the harassment is by a supervisor or co-workers (if a supervisor is the harasser, the claimant has an easier path); and (2) whether the employer has an anti-harassment or similar policy to prevent such actions (if so, the employer-defendant is typically in a better position).2 Recently, in Vance v. Ball State University, the U.S. Supreme Court defined a "supervisor" for purposes of Title VII claims as someone "empowered by the employer to take tangible employment actions against the victim."3 Vance narrows the definition of "supervisor" in a way that benefits employers (see the discussion below).

In University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, the Court held that retaliation claimants must show that "but for" the employer's intent to retaliate, the complained-of action would not have occurred.4 This is a higher burden than most Title VII claimants - i.e., those suing for other types of employment discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, and national origin - must meet. In those cases, the claimant need only show that the discrimination was one of a number of motives for the complained-of action, not the only reason he or she was fired, demoted, or the like.5

Though these recent Supreme Court cases are victories for employers, they also reflect the increase in such claims and the special challenges they raise for employers.6 These challenges remain even after Nassar and Vance.

This article gives an overview of the law of hostile work environment harassment and retaliation, and the impact of these cases. It then looks at why employers should create clear supervisory structures and effective anti-harassment policies that stand them in good stead before a claim arises, and offers some suggestions for drafting good policies. Not only can they help prevent harassment and retaliation claims, they can lead to a more productive and appealing workplace.

Hostile work environment claims

The challenge for employers. In the typical discrimination claim, the claimant must allege an adverse employment action - e.g., a termination, suspension, demotion, or failure to hire or promote.7 "Otherwise, every trivial personnel action that an irritable, chip-on-the-shoulder employee did not like would form the basis of a discrimination suit."8

But an exception to this rule was carved out for "hostile work environment" harassment claims. For those, a claimant may state a claim by alleging harassment severe or pervasive enough "to alter the conditions of [the victim's] employment and create an abusive working environment."9 Comments, pranks, and other inappropriate workplace misbehavior are sometimes enough to render an employer liable to its employee under a hostile work environment theory.

Alleged hostile work environments can be difficult to prove or disprove, especially under the standard at summary judgment. Courts have continued to accept that Title VII is not a "general civility code," and a few inappropriate comments do not constitute a hostile work environment.10

But what does? The seventh circuit has repeatedly acknowledged that "drawing the line is not always easy" between normal office banter and a hostile work environment.11 And just as difficult is deciding when the employer is responsible - and thus liable - for that environment.

Adding to employers' challenges is the reality that harassment claims make ideal "defensive filings" by employees with performance or behavioral problems who expect discipline in the future. The cost-free filing may have a deterrent effect on sensitive or claim-adverse managers. And if the discipline occurs, the temporal proximity to the harassment claim - which itself might not be strong enough to withstand summary judgment - could possibly support a follow-up retaliation claim.12 Indeed, the Nassar Court noted the problem of defensive filings in its decision.13

The Faragher/Ellerth test. In 1998, in an effort to bring structure to hostile work environment claims, the U.S. Supreme Court decided the twin cases of Faragher and Ellerth. These cases premised the liability of an employer largely on two core questions: (1) whether the harassment comes at the hands of a supervisor14 (which strengthens the employee-claimant's hand); and (2) whether the employer had, and the employee used, a method for making and resolving internal complaints (which strengthens the employer's position).15 The Court expressly noted Title VII's preventative role and tried to encourage good employer behavior by tying liability to the employer's internal procedures for resolving harassment.16

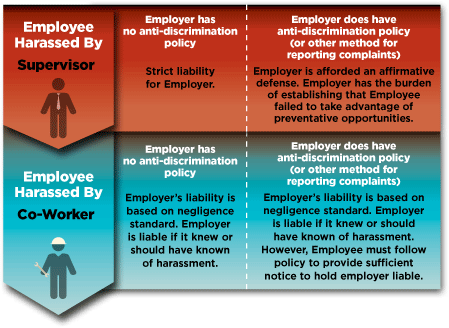

Under the Faragher/Ellerth test, assuming an employer who has taken no tangible employment action (e.g., termination) and who reasonably acts to correct harassment once notified, the rubric for employer liability for Title VII hostile work environment claims can be illustrated by the figure on the following page.

The difference between supervisor and co-worker harassment is even stricter at the state level in Illinois. Under the Illinois Human Rights Act ("IHRA"), employers are always strictly liable for supervisory harassment and have no affirmative defense like the one set out in Faragher and Ellerth.17 Liability for co-worker harassment is more similar: an employer is liable if it "becomes aware of the conduct and fails to take reasonable corrective measures."18

The importance of anti-harassment policies. The advantage to employers of having a good anti-harassment policy is evident in the Faragher/Ellerth chart. Even under the lower negligence standard for hostile work environments created by co-workers, the employee must give notice to someone "with authority to take corrective action or, at a minimum, someone who could reasonably be expected to refer the complaint up the ladder to the employee authorized to act on it."19

The importance of anti-harassment policies. The advantage to employers of having a good anti-harassment policy is evident in the Faragher/Ellerth chart. Even under the lower negligence standard for hostile work environments created by co-workers, the employee must give notice to someone "with authority to take corrective action or, at a minimum, someone who could reasonably be expected to refer the complaint up the ladder to the employee authorized to act on it."19

"If the employer has established a set of procedures for reporting complaints about harassment, the complainant ordinarily should follow that policy in order to provide notice sufficient for the employer to be held responsible, unless the policy itself is subject to attack as inadequate," the seventh circuit has written.20 In contrast, when an employer does not have a policy in place, the door opens wide for any number of arguments about which employees should have been "reasonably expected" to relay a complaint.

The seventh circuit case Lambert v. Peri Formworks Systems, Inc., decided a month after Vance on July 24, 2013, illustrates the danger of not having an anti-harassment policy. In Lambert, the employer instituted its formal anti-harassment policy sometime after the employee-claimant had first relayed harassment complaints to two "yard leads" - higher-ranking co-workers who were not supervisors under Vance.21

The court found that because the formal policy was not yet in place when the employee first complained, his failure to use the procedure later could not absolve the corporation of responsibility, particularly because his earlier (and futile) informal complaints might have discouraged further efforts.22 Thus, the lack of a policy helped the plaintiff escape summary judgment.

Vance narrows the definition of supervisors. Before Vance, a number of federal circuits and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission had ruled that a "supervisor" for purposes of harassment claims was anyone who directed some of the daily activities of another employee.23 The seventh circuit used a narrower definition: a "supervisor" is someone who can take tangible action (i.e., the same type of employment action required in most discrimination claims) against the employee.24 This set up a showdown in the Supreme Court between the two tests, and many expected the Court to choose the less stringent "daily activities" approach.

Instead, Vance affirmed the seventh circuit, bringing much-needed clarity to the definition of "supervisor," and through it, to harassment claims. The Court dismissed the "daily activities" test as a "study in ambiguity" and expressly affirmed the seventh circuit test for its clarity and ability to resolve material issues before trial.25

After Vance, an employer need no longer fear that disputes over the extent of an underling's authority will make the difference between summary judgment and trial. More importantly, for an employer who has not clearly established and communicated its supervisory relationships, the Vance decision is a very good reason26 to do so. Any employer who fails to clearly establish its supervisory relationships post-Vance is walking into an avoidable strict liability trap.

Supervisory structures and anti-discrimination policies in retaliation claims

We now turn to retaliation claims and examine the preventative role that good anti-discrimination policies and well-designed supervisory structures can play.

To state a claim for retaliation, a claimant must generally show that: (1) he or she engaged in a statutorily protected activity (e.g., filing a discrimination claim); (2) he or she suffered a materially adverse employment action; and (3) a causal connection exists between the two (which can be shown in a number of ways).27 Post-Nassar, a retaliation claim requires a claimant to demonstrate that a "protected activity" under Title VII was a "but-for" cause of an alleged adverse action by his or her employer.28

Note that a "protected activity" for purposes of a retaliation claim is not limited to bringing a formal Title VII (or IHRA) proceeding. Internal complaints of discrimination can sometimes support a claim for retaliation.29 Whether an informal statement or complaint constitutes a protected activity is precisely the type of thorny question of fact that can complicate a retaliation case at summary judgment.

Having a good anti-discrimination policy, with clear channels for reporting complaints, helps avoid such complicated questions. Several courts have found that a claimant who failed to follow a formal reporting procedure did not engage in "protected activity."30

The clear reporting channels of an anti-discrimination policy can also prevent retaliation claims - and, indeed, retaliation - in another way: by preventing people at the company who should not be informed from knowing about the report. Quite simply, someone cannot retaliate against an employee if they are unaware of the protected activity.31

Crafting effective anti-discrimination and harassment policies

Having underscored the importance of employers having an anti-harassment policy and a clear supervisory structure, it is only appropriate to discuss a few factors to consider in creating these types of policies.

Anti-harassment and discrimination policies. An employer looking for a quick harassment policy template should be able to find one. As of the date of this article, for instance, the Illinois Department of Human Rights posts a sample on its website.32 But as Lambert and other cases demonstrate, the policy should be tailored as needed to the individual workplace to withstand challenge. In designing the reporting relationships for an effective policy, the following factors are important:

• Clearly describing the appropriate reporting channels to employees.

• Making the reporting channels easily accessible to employees. If the only designated reporting channels are offsite, for example, the door may be open for an attack on the employer's policy as unreasonable.

• Bringing the matter, as quickly as possible, to a person who understands the nature and contours of discrimination and harassment claims, including retaliation, and how to address, investigate, and respond to complaints as they arise.

• Avoiding unnecessary dissemination of information about such claims, which often includes setting up reporting channels outside the normal command structure.

• In addition to establishing reporting channels for employees, employers should consider reminding those in the normal command structure - particularly "supervisors" under Vance - to route information into the designated reporting channel and not to retaliate. This may avoid situations like Lambert, where an employer was held responsible for informal complaints that died at the lower level, even though it had later set up a reporting policy, because evidence suggested that it had accepted such informal complaints.

Finally, a word on distributing anti-harassment policies (or indeed, any workplace rules): have the employees sign a confirmation of receipt of the policy. Courts will attribute constructive notice of a policy's contents to an employee who has received it, and the signed receipt will keep the dissemination of the policy itself from becoming a disputed question of fact.33

A word about supervisory relationships. Regarding an employer's supervisory structure there is less to say. But certainly employers should be warned not to concentrate decision-making too far up the command structure. As Vance warned, doing so may open the door to the "cat's paw" argument - that a far-removed supervisor simply "rubber stamps" the decision of a biased lower-level employee,34 and thus the employer should be liable despite the supervisor's lack of ill intent.

This article will not discuss the "cat's paw" doctrine in depth (for more on that, see "The Cat's Paw Theory in Illinois after Staub," by Alexandra Lee Newman and Yelena Shagall in the February 2012 IBJ). But where a proper supervisor is identifiable, courts will often be reluctant to apply the "cat's paw" doctrine or to go beyond de jure organizational structures of a corporation.35

Daniel Myerson is an assistant corporation counsel at the City of Chicago's Department of Law, Labor Division. Before that he was an associate at the Law Offices of Michael Murphy Tannen, P.C. He is a graduate of Loyola University Chicago's School of Law.

- 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.

- Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775 (1998); Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742 (1998).

- Vance v. Ball State University, 133 S. Ct. 2434, 2454 (2013).

- University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, 133 S. Ct. 2517, 2533 (2013).

- See 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(m).

- The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) received 38,539 retaliation claims in 2013 (up from 18,198 in 1997). U.S. Equal Emp't Opportunity Comm'n, Retaliation-Based Charges FY 1997 - FY 2013, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/retaliation.cfm. In 2011, the EEOC or its state partners received 30,512 harassment charges (up from 23,047 in 1997). U.S. Equal Emp't Opportunity Comm'n, Harassment Charges EEOC and FEPAs Combined: FY 1997 - FY 2011, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/harassment.cfm. In Illinois, 5,490 charges were filed with the EEOC in 2012. U.S. Equal Emp't Opportunity Comm'n, EEOC Charge Receipts by State (includes U.S. Territories) and Basis for 2012, available at http://www1.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/state_12.cfm?redirected=http://www.eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/. Given the Department of Labor's figure of 5,640,740 total employees in Illinois, one can draw a (very rough) estimate of 1 charge of discrimination, per year, for every 1,000 employees. See U.S. Dep't Labor, May 2012 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates - Illinois, available at http://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes_il.htm.

- Herrnreiter v. Chicago Housing Authority, 315 F.3d 742, 744 (7th Cir. 2002).

- Id. at 745.

- Meritor Savings Bank, FSB v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 67 (1986).

- Faragher v. City of Boca Raton, 524 U.S. 775, 788 (1998).

- Hostetler v. Quality Dining, Inc., 218 F.3d 798, 807 (7th Cir. 2000).

- See, e.g., Loudermilk v. Best Pallet Co., 636 F.3d 312, 315 (7th Cir. 2011).

- University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, 133 S. Ct. 2517, 2532 (2013).

- Burlington Industries, Inc. v. Ellerth, 524 U.S. 742, 764-65 (1998).

- Faragher, 524 U.S. at 805-07.

- Id.

- Webb v. Lustig, 298 Ill. App. 3d 695, 705 (4th Dist. 1998).

- 775 ILCS 5/2-102(D).

- Lambert v. Peri Formworks Systems, Inc., 723 F.3d 863, 866-67 (7th Cir. 2013) (quoting Parkins v. Civil Constructors of Illinois, Inc., 163 F.3d 1027, 1037 (7th Cir. 1998)).

- Id. at 867; see also Durkin v. City of Chicago, 341 F.3d 606, 613 (7th Cir. 2003) (informal and general complaints to co-workers insufficient, where policy not followed).

- Lambert, 723 F.3d at 867-68.

- Id.

- See, e.g., Mack v. Otis Elevator Corp., 326 F.3d 116, 126-27 (3d Cir. 2003); Whitten v. Fred's, Inc., 601 F.3d 231, 245-247 (4th Cir. 2010); U.S. Equal Emp't Opportunity Comm'n, Enforcement Guidance on Vicarious Employer Liability for Unlawful Harassment by Supervisors, available at http://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/harassment.html (last visited Feb. 14, 2014).

- Rhodes v. Illinois Department of Transportation, 359 F.3d 498 (7th Cir. 2004).

- Vance v. Ball State University, 133 S. Ct. 2434, 2449-50 (2013).

- There are other good reasons to clearly communicate supervisory relationships, even just in more traditional Title VII claims. To give one example, an employee's job description and supervisor are both factors used by a court to identify "similarly situated" employees. Salas v. Wisconsin Department of Corrections, 493 F.3d 913 (7th Cir. 2007).

- Tomanovich v. City of Indianapolis, 457 F.3d 656, 663-66 (7th Cir. 2006).

- University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center v. Nassar, 133 S. Ct. 2517, 2533 (2013).

- Tomanovich, 457 F.3d at 664.

- See, e.g., Rhodes v. Illinois Department of Transportation, 359 F.3d 498, 508 (7th Cir. 2004).

- See, e.g., Stephens v. Erickson, 569 F.3d 779, 789 (7th Cir. 2009).

- Ill. Dep't Human Rights, Model Employer Sexual Harassment Policy, available at http://www2.illinois.gov/dhr/PublicContracts/Pages/Sexual_Harassment_Model_Policy.aspx (last visited Feb. 14, 2011).

- See Shaw v. Autozone, Inc., 180 F.3d 806, 811-12 (7th Cir. 1999).

- Vance v. Ball State University, 133 S. Ct. 2434, 2452 (2013).

- See Andonissamy v. Hewlett-Packard Co., 547 F.3d 841, 849 (7th Cir. 2008).