February 2016 • Volume 104 • Number 2 • Page 22

Thank you for viewing this Illinois Bar Journal article. Please join the ISBA to access all of our IBJ articles and archives.

Practice Management

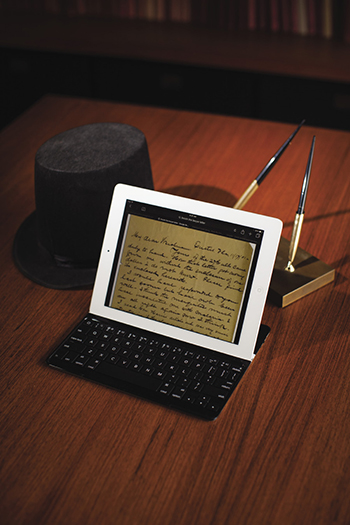

Lincoln and Herndon 2016

If Abraham Lincoln were practicing today, what management techniques and tech tools would - or should - he and partner William Herndon use? Our 21st Century experts offer advice.

If Abraham Lincoln were alive and lawyering in 2016 - assuming his practice itself otherwise stayed the same - what practice management techniques and technology tools would he and partner William Herndon use? Although there's no way to say for certain, our 21st century management and technology experts had fun sharing their prognostications.

If Abraham Lincoln were alive and lawyering in 2016 - assuming his practice itself otherwise stayed the same - what practice management techniques and technology tools would he and partner William Herndon use? Although there's no way to say for certain, our 21st century management and technology experts had fun sharing their prognostications.

While most Americans identify Lincoln almost entirely as our 16th President, the iconic leader who won the Civil War and freed the slaves, Illinois attorneys are well aware that he spent a quarter-century before entering the Oval Office as a hard-riding member of their ranks who rose to the top of his profession on the nation's frontier.

Lincoln first joined John T. Stuart as a junior partner in 1836, became partner with Stephen T. Logan in 1841, and then split from Logan and took Herndon as his own junior partner in 1844. It is with Herndon that he is best known for practicing law, according to Abraham Lincoln Online. Lincoln's practice took a back seat to serving as a U.S. congressman from 1847-49 before he returned to Springfield full time until being elected President.

Like most attorneys at the time, Lincoln and his partners were general practitioners and represented companies and people from all walks of life. They usually represented clients at the circuit court level in either common law or chancery cases, although appellate and even supreme court cases at both the state and federal level were not unheard of.

Lincoln's docket occasionally also included criminal, bankruptcy, and probate cases, according to Abraham Lincoln Online. He represented a handful of larger clients like railroad companies but mostly smaller clients.

While Herndon typically stayed in their offices in Springfield, Lincoln rode the state's Eighth Judicial Circuit in east-central Illinois about six months of the year, Abraham Lincoln Online says. In his letters of advice to young lawyers, he instructed a couple of them that he would not make a suitable mentor to them - most attorneys at the time studied under a senior lawyer rather than attending formal law school - because, as he said to one, "I am from home too much of the time."

While on the road, Lincoln traveled by horseback and later train, kept case files and law tomes in a briefcase or other satchel, and he communicated with Herndon and others back in Springfield by what we now call "snail mail" or perhaps, later in his practice, the telegraph. Samuel Morse's invention first made its appearance on Aug. 24, 1844, with the famous initial transmission, "What Hath God Wrought?"

Travel-ready hardware

It's unclear what Morse - or Lincoln - would have exclaimed about Twitter, even if Morse's initial transmission came in well below 140 characters. But if Lincoln and his practice were transported 160 years forward in time, a significant amount of his adjustment would revolve around the changes in mobile technology in the 21st century, says Bryan Sims of the Sims Law Firm Ltd. in Naperville and the ISBA's Committee on Legal Technology.

"Obviously you're looking at some sort of laptop. Probably you want one that's fairly [easy to transport]; not a huge, heavy one," Sims says. "You'd want a smart phone and a tablet, as well. I'd certainly use that all of the time." Sims sees the smartphone as, first of all, important for phone calls, although that's become a less common way of communicating than texts or e-mails. The laptop would help Lincoln produce documents, which is harder to do on a smartphone or tablet.

"Where you're outside of the office, you can draft pleadings, or motions, or whatever it is that you need to do," he says. "A lot of times, if you're traveling, you've got some down time involved, before or after court, or in between court appearances, where you can get work done while you're waiting."

The tablet would fall in between the phone and laptop, providing the ability to accomplish pieces of an attorney's work that isn't as easy to do on one of those other devices, Sims says. "It's really good for things like legal research, an extensive handling of your e-mail, review and markup of documents, that sort of thing - without having to get your laptop out, start it up, and find a place to plug it in," he says.

Jim Calloway, director of the management assistance program at the Oklahoma Bar Association (and occasional ISBA presenter), recalls that Lincoln could not make a living just practicing law in one town because the court only met for a few weeks at a time, which is why he ended up riding the circuit - a set of circumstances that obviously has changed in the early 21st century.

But if he still had a need to visit multiple courthouses - and many of today's Illinois lawyers do - Calloway agrees with Sims that mobile devices would be critical to his practice. "He would definitely have a smart phone, and he would definitely have some sort of Internet access for his laptop or his tablet, wherever he was, on the road" he says. "That's true for today's lawyers. We are so busy with our schedules, we have so much work that needs to be done, those mobile devices, when you have 10 minutes to spare, are still a pretty important part of the practice."

Natalie Kelly, director of the law practice management program at the Georgia State Bar Association and a presenter at the ISBA Solo and Small Firm Practice Institute in September, believes Lincoln would have been excited at the array of devices available in 2016 given his love of inventions and the search for solutions to the problems of society and the law. "He would probably say, 'I'm going to try that new tablet,' and it would be a fight between a Surface Pro and an iPad," Kelly says.

Lincoln would want strong passwords on his phone and tablet to keep those devices from being breached and to set them up so that they could be remotely "wiped" if he lost them while riding the circuit, Sims says. And to ensure security of his laptop, Lincoln would want whole disc encryption.

"That's an absolute must, I think," he says. "If you happen to lose it, having it fully encrypted means that somebody's probably not going to be able to get into it." Probably the best option for doing so is the BitLocker function that's built into the Professional version of Windows 8 or 10. "That's makes it easier to use [encryption]," he adds. "You don't have to go out and get a third party program."

Tech at the office

While back in the office in Springfield, Lincoln wouldn't need to use his road-warrior technology so much although he certainly would be using his cloud storage, Sims says. Herndon could use whatever computer he wanted and Lincoln could connect his laptop to a full-size keyboard and monitor, but there would be no need for an in-office server thanks to the Internet-based cloud. "It's not like you need a bunch of extra equipment," he says.

Lincoln and Herndon probably would set up their office with a voice system with a forwarding function rather than a traditional land line. "Not only does Herndon have access to that for the office phone, but when Lincoln's out, all those services let you forward your calls to your [cell] phone when you're out - or when they go to voicemail, it sends an e-mail that [says] 'hey, you just got a voicemail,' which is useful for everybody involved."

Apps and the cloud

While on the road, Lincoln might well have tucked Blackstone's Commentaries into his saddlebag. Today he'd be need access to thousands of reported cases and voluminous texts. But Sims points out that in the 21st century he could have access to such legal research at the touch of a device button, likely a phone or tablet.

Sims says apps as a quick link to legal research, such as Fastcase, although he recommends an app called Caselaw. "I used it in court this morning," he says. "It allows you to purchase particular sections of either your state statutes, or federal statutes or codes. It allows you to access them on your device without necessarily being connected." Lincoln could access, as Sims has done, the Illinois Code of Civil Procedure or Illinois Rules of Evidence. "I can get to them easily and pull up a particular statute, and have it at my fingertips," he says.

"There's got to be some way that [Lincoln and Herndon are] using the cloud to share documents," he says. "Traveling among several counties, you need to be able to access your documents when you're outside the office. And then some sort of practice management software, which everybody should have, probably cloud-based."

Cloud services often come with built-in apps for the phone or tablet, Sims says, whether for practice management software or shared office files, available with a couple of clicks. Lincoln would want hosted e-mail and a shared office environment through the cloud, through such services as Google Apps for Business or Microsoft Exchange. This would enable him and Herndon to connect not only via e-mail but also offer other functions like calendaring. "If you're using some sort of hosted exchange server, you can give permissions to each other to access mail if you're going to be on vacation, so that one can easily cover for the other," he says.

Cloud-based document storage would relieve Lincoln of the need to stuff all his case matters into his heavy leather briefcase, Kelly says, and instead of asking "how long do we have to keep this?" the matters could be kept forever in cyberspace. "That [also] becomes cloud-based storage and then disaster recovery [if needed] so I can get back those documents."

Calloway characterizes Lincoln as "a man of his times, but [he] also looked ahead and was very forward-thinking," which means that "I am confident that Lincoln and Herndon would have practice management tools to organize their files," he says. He agrees that this might include everything from an iPhone app with Blackstone's Commentaries to cloud-based storage.

Also available in the cloud would be document assembly solutions like ISBA's IllinoisDocs forms system. Lincoln and Herndon would want to use document assembly, Kelly says. "That would be something for them to be cognizant of - if it's the same fight over the cows coming onto our land, we've seen this [type of case] over and over again, having a system where we can be repetitive, to be working toward efficiency, would be something to think about. That leads to the different document assembly tools available to lawyers."

Billing and tracking

Lincoln and Herndon would want to avail themselves of billing and tracking software, most likely in the cloud, Kelly says. "Organization is going to be required for them to keep up and keep track, especially with Lincoln traveling around," she says. "If you started with just the basics of getting paid, it's kind of interesting because [they would need]…to keep up with how much have I invested in this? How much time have I invested in these types of cases? How much should be given to railroad cases versus multiple smaller matters?"

Aside from the technology aspect, Lincoln and Herndon would need to adjust their billing to an hourly basis in many cases, although Kelly notes that in the early 21st century, some attorneys and firms are coming full circle to the kind of flat fees Lincoln charged, at $300 for one type of case or $75 for another. In addition to adjusting for inflation, Lincoln would need to institute time-tracking software, she says. "That leads to the general concept of matter management: How do you keep up with all these cases?"

Calloway believes that adjusting to timesheets and charging by the tenth of an hour would be perhaps the most difficult change for Lincoln to make if he were transported to the present day. "I don't know how easy he would be able to deal with that," he says. Lincoln might also have difficulty with the modern-day concept of asking for a significant retainer upfront before starting a case.

"In fact, he's quoted as telling [fledgling lawyers] never to take your whole retainer in advance," Calloway says. "I have a feeling if he were practicing in today's environment, he might have to change his attitude. His thought was that once you get all the fee upfront in a case, that you lose interest in it. He saw that happen many times." And Calloway quotes Lincoln directly: "When fully paid beforehand, you're more than a common mortal if you feel the same interest in the case."

Lincoln also might be surprised at some of what goes into trying cases, Calloway believes. "He would be shocked at some of today's practice," he says. "The idea of doing all this discovery would be a big adjustment." Back then, lawyers often showed up in the county seat and tried their cases almost immediately after meeting with clients.

Modern-day legal ethics, work ethic

Although known to history as "Honest Abe," Lincoln would need to navigate unfamiliar conflict-of-interest rules, given that the Illinois Rules of Civil Procedure did not come into place until the early 20th century, Kelly says.

"I don't know...how that would be approached," she says. "I'm representing a railroad; does that preclude me from representing the bank? It boils down to the personal relationships that lawyers now have, and having to manage those from the marketing side. And practice management systems, they're so comprehensive, we keep circling back to those; they have components for firms to manage referrals. How did this business get to us?"

Lincoln would view competence in modern technology as an ethical must, Calloway believes. "The same way as he used Blackstone's Commentaries as his tool of the trade, he would think the technology we have today is a very important tool of the lawyer's trade."

Ultimately, Lincoln would adjust easily enough to his century and a half of time travel because he believed in timeless lawyerly values, Calloway says. "He believed in doing good work for your client, and getting paid for that good work, and being a diligent lawyer," he says. "I am sure that he would be an advocate of keeping good client communications, whatever that took. That's something lawyers were probably challenged with back in Lincoln's day and are still challenged with today.

"Lincoln was a believer in honesty, and trust and integrity," he adds. "It would be standard hard work, good client service, and honesty and integrity. Those are timeless values that would serve Lincoln well in today's environment."

Ed Finkel is an Evanston-based freelance writer.

edfinkel@earthlink.net